David Eddy, chair of Foxholes and Butterwick Parish Council, in North Yorkshire, reports on the challenges facing local communities dealing with oil and gas developments.

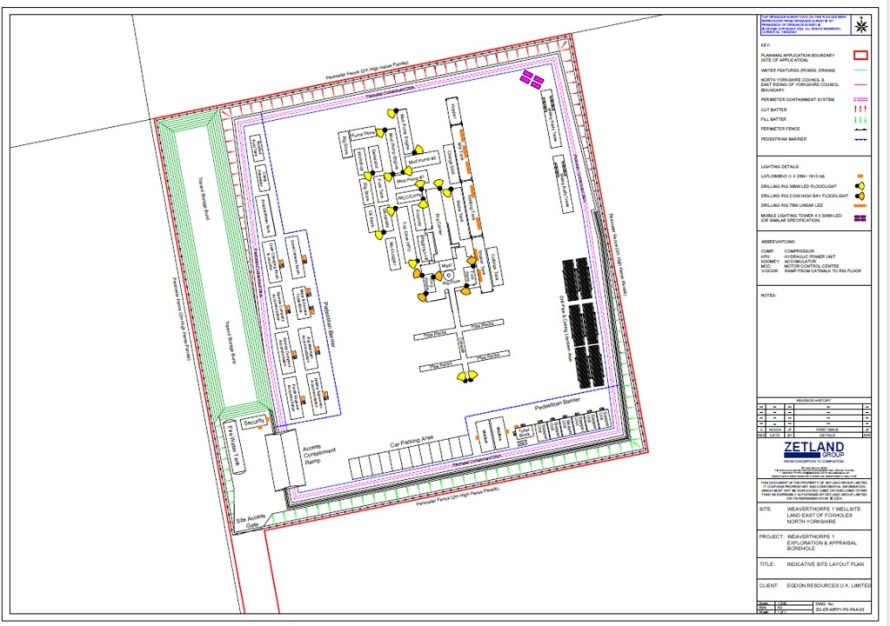

Foxholes & Butterwick Parish Council (F&BPC) is currently immersed in a complex planning and regulatory process for a gas drilling application in Foxholes. This is the first time we have had to grapple with such a wide-ranging and highly technical submission from an energy company.

The following are personal observations, as chair of F&BPC, about the planning regulations and processes, particularly how they affect local communities facing major energy proposals.

We are only at the planning application stage thus far, but already there is much to unpick.

An unequal system

Current planning regulations, both locally and nationally, are heavily weighted in favour of developers. In the case of energy applications, this imbalance overwhelmingly benefits large companies at the expense of local communities who bear the risks and long-term consequences.

Historic planning policies still provide preferential treatment to oil and gas extraction. This is now entirely at odds with national priorities on net zero, renewable energy, and climate science. The imbalance requires urgent reassessment.

Fragmented oversight and accountability

Offshore drilling in the UK is subject to tight, well-coordinated regulation. By contrast, onshore drilling oversight is fragmented among multiple regulators, including the Environment Agency (EA), Health & Safety Executive (HSE), and North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA). Each focuses narrowly on its own specialist remit.

No single authority has sight of all documentation, meaning crucial risks can “slip through the net”. If the Local Planning Authority (LPA) refuses an application, the developer can appeal to the Planning Inspectorate (PINS). Yet PINS will not automatically see the documents submitted separately to other regulators, unless specifically requested. Developers therefore benefit from a lack of transparency and can selectively disclose information.

Lack of access to Information

Statutory consultees, parish councils and the public are routinely denied access to key documents until after the planning consultation period closes. This prevents meaningful scrutiny and engagement.

For example, F&BPC requested three documents:

- Construction Management Plan;

- Non-Technical Summary

- Chemical Inventory.

All of which were refused by the developer.

The refusal to provide a Non-Technical Summary is particularly concerning. This basic explanatory document should be required for all major or technical applications, regardless of whether an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is formally triggered.

Developers often claim to be committed to community engagement, yet fail to provide accessible information. Without plain language summaries, local residents cannot reasonably be expected to fully understand the proposal’s implications. This leaves communities voiceless and disempowered.

Mitigation, enforcement, and trust

The concept of “mitigation” dominates planning and regulatory practice for onshore drilling. Yet mitigation does not mean elimination of risk, only the attempt to lessen it. Communities are right to doubt whether mitigation measures will be enforced effectively.

Regulators such as the EA and LPAs are significantly under-resourced (unlike developers), with limited capacity for on-site monitoring. In some cases, companies monitor their own compliance or commission “independent” contractors paid directly by them. This practice is akin to “marking their own homework” and undermines public trust. Numerous examples across the UK show not only breaches of planning or permit conditions, but these going unsanctioned too.

Mitigation without robust enforcement offers false reassurance and leaves communities exposed to residual risks to groundwater, soil, landscape, and public health. Nor can local mitigation offset the global climate impacts of continued fossil fuel extraction.

Burden of proof and resource inequality

In theory, developers must demonstrate policy compliance, and LPAs must verify it before determining applications. In practice, however:

- Developers employ consultants, lawyers, and planners to produce hundreds of pages of polished documentation.

- LPA’s, under intense resource pressure, rely heavily on the applicant’s evidence.

- Communities and parish councils lack equivalent expertise or funding.

Objections from residents are often dismissed as “non-material” unless precisely referenced to planning policy. This system privileges the technically literate and leaves ordinary communities structurally disadvantaged. Parish councils like F&BPC, with no budget for consultants or lawyers, face impossible barriers to meaningful participation. Some form of training, guidance, or financial assistance from LPAs is essential if communities are to engage effectively.

Independence and credibility of supporting documents

Many technical reports submitted by applicants are produced by consultants whose financial survival depends on repeat business from industry clients. This creates a serious conflict of interest and undermines the credibility of their findings.

For example, in the Foxholes gas drilling application, the developer’s own Hydrogeological and Flood Risk Assessment (HRA), openly states that it relies on client provided data and contains no site-specific testing. It assumes that containment systems will perform flawlessly, despite the design not yet being finalised, and offers no contingency for failure, extreme weather, or cumulative effects. This omission is contrary to National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), paragraph 183, on pollution prevention.

It is but one of a multiplicity of examples across a range of supporting documentation. Such omissions demonstrate why assessments prepared by commercially- dependent consultants cannot be treated as independent or comprehensive evaluations of environmental risk.

Such documents often focus on best case scenarios while ignoring cumulative effects, long-term risks, or broader climate impacts. Communities are rightly sceptical when “independent” assessments appear to favour the applicant.

All environmental and risk assessments should be commissioned or peer reviewed by genuinely independent bodies, not directly contracted by proponents. Greater weight should be given to community submissions, academic research, and cumulative impact studies.

Recommendations

To restore public confidence and level the playing field, a number of reforms are needed.

For Local Planning Authorities

- Publish all application materials, including those shared with other regulators, at the outset of consultation. This requires updating of the Planning Checklist.

- Require a Non-Technical Summary for all complex energy applications.

- Provide early-stage training for parish councils and community representatives on planning procedures and policy referencing.

- Extend consultation periods for multi-agency or technically complex applications.

- Establish modest support funds to help local councils commission professional planning or environmental advice.

- Strengthen enforcement capacity and publish compliance reports transparently and regularly.

For Regulators and the Government

- Review national planning policy to remove outdated preferential treatment for fossil fuel extraction.

- Create a unified framework for onshore energy regulation to ensure full oversight and data sharing between agencies.

- Fund independent peer reviews of technical documentation.

- Establish a Community Planning Support Unit within PINS or Department of Levelling Up Housing & communities (DLUHC) to advise local councils and residents.

- Require genuine, auditable community engagement plans as part of all major energy applications.

For Developers

- Provide plain language summaries and accessible visual materials for all proposals and all stakeholders.

- Share all relevant documents openly at the start of consultation.

- Commission independent third-party verification of key risk assessments.

- Fund local environmental monitoring through LPAs or the EA, not self-reporting systems.

Conclusion

The current planning system privileges well resourced developers and leaves local communities struggling to make their voices heard. Transparency, independence, and genuine engagement are the foundations of trust, yet all three are lacking.

It is like playing a board game, with another, hitherto unknown, rule announced after we’ve rolled the dice.

Communities like ours do not oppose development for its own sake; we ask only for fairness, access to information, and the ability to protect our environment with equal footing.

Until these systemic issues are addressed, planning for onshore energy projects will continue to feel less like a democratic process and more like an endurance test for those who care most about the places they live.

Categories: guest post, slider