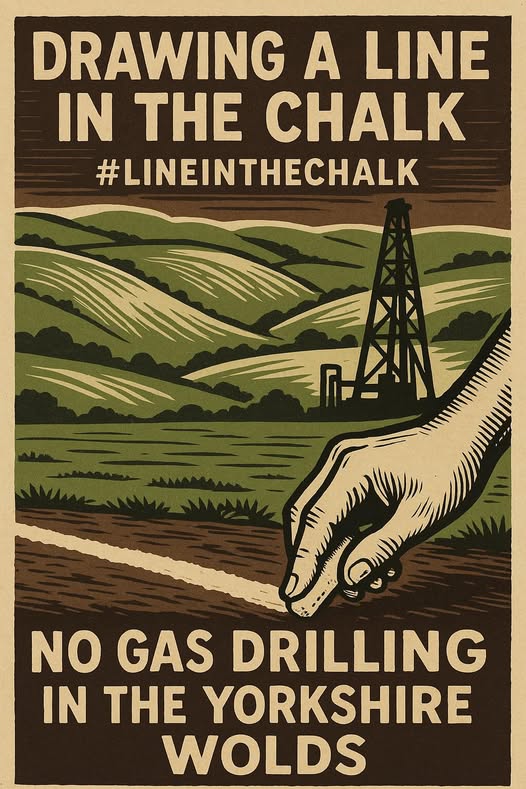

In this guest article, David Eddy examines Yorkshire Water’s response to plans to drill for gas at Foxholes in North Yorkshire, above one of the region’s main sources of drinking water. Mr Eddy is a member of the Drawing a Line in the Chalk Steering Group, which is campaigning against the proposals by the oil and gas company, Egdon Resources.

Yorkshire Water exists to protect and supply safe drinking water. A fundamental public service and statutory responsibility. This duty extends beyond mere supply to safeguarding the precious groundwater resources on which entire communities depend today and for generations to come.

Yet, paradoxically, in its formal response to Egdon Resources’ proposed gas drilling near Foxholes (planning reference NY/2025/0113/FUL), Yorkshire Water raises no objection. This is despite acknowledging that the development is proposed directly above one of the most sensitive and vulnerable groundwater systems in the region, the Principal Chalk Aquifer. This apparent contradiction is not just puzzling but deeply concerning, and it demands urgent public scrutiny.

The vulnerability of the principal chalk aquifer

The proposed drilling site sits atop the Flamborough Chalk Formation, officially designated by the Environment Agency as a Principal Aquifer. This classification is reserved for groundwater bodies of exceptional strategic importance. This Principal Aquifer provides drinking water to nearly one million residents of East Riding and surrounding areas and supports fragile ecological networks dependent on clean and standard water supplies.

Yorkshire Water’s own consultation response explicitly confirms the aquifer’s vulnerability. It states there are no superficial deposits protecting the chalk at this location, meaning the aquifer is “highly vulnerable to pollution from activities at the surface.” In addition, it highlights that deep boreholes, such as those proposed in this application, can create direct pathways for pollutants to enter the aquifer, bypassing natural filtration.

Crucially, the site lies within a Source Protection Zone 3 (SPZ3). A catchment area established to protect groundwater abstractions used for public water supply. These zones exist because groundwater contamination does not respect administrative boundaries or planning conditions. Once pollutants penetrate a chalk aquifer, they can travel for kilometres along fracture networks, persisting for decades or longer due to slow natural attenuation.

Yorkshire Water acknowledges all these risks. It recognises that protecting the aquifer depends on multiple technical safeguards:

- effective casing of the borehole;

- impermeable membranes to prevent leaks;

- bunded storage tanks for drilling fluids;

- controlled drainage systems to avoid runoff;

- careful handling of fuels and chemicals and;

- a robust decommissioning strategy to avoid long term pollution pathways.

However, none of these safeguards are guaranteed upfront. Instead, Yorkshire Water relies heavily on planning conditions to secure them after permission is granted, leaving crucial details unavailable for scrutiny during consultation.

Procedural deferral versus genuine protection

This reliance on future mitigation measures, often secured through planning conditions, reflects a familiar and problematic pattern in infrastructure planning: acceptance in principle, conditional on everything going perfectly right thereafter.

Yorkshire Water’s response notably “notes” the applicant’s Hydrogeological Risk Assessment (HRA), which concludes that risks to the aquifer would be “low following mitigation.” However, there is no evidence that Yorkshire Water has independently verified, peer reviewed, or critically challenged this assessment. This is significant because accepting risk on the basis that mitigation measures will function as intended, and enforcement will be effective, is a high stakes gamble. History has shown that accidents, human error, and equipment failures do occur.

Moreover, the applicant’s HRA is itself incomplete. A formal objection submitted by Foxholes & Butterwick Parish Council points out that the HRA does not incorporate recent British Geological Survey (BGS) remapping of the Yorkshire Wolds. Critical updated geological information aimed specifically at better understanding the chalk aquifer’s fracture networks and groundwater flow. In fractured chalk geology, such data is essential for accurately assessing potential pollution pathways. Relying on legacy geological interpretations means proceeding with incomplete knowledge and underestimating risk.

Yorkshire Water was made aware of this challenge but has not amended its position. This contrasts with its own stance in 2013 when it objected to a similar nearby drilling proposal that was subsequently withdrawn due to risk concerns. The aquifer’s geology and vulnerability have not changed, but Yorkshire Water’s threshold for acceptable risk appears to have shifted without clear explanation or justification.

The language Yorkshire Water uses is another concern. Terms like “should be attached” or “should include” imply advisory recommendations rather than firm requirements. These may be interpreted by planning officers as tacit support contingent on later compliance. This creates reassurance without protection and blurs the line between technical advice and regulatory objection.

Institutional responsibility and risk normalisation

It is important to recognize that Yorkshire Water operates as a private company within a regulatory framework largely focused on procedural compliance and risk documentation. This structure incentivises risk management, mitigating and monitoring risks, rather than outright risk avoidance.

But groundwater contamination is fundamentally different from many other environmental impacts. Pollution of a chalk aquifer from either surface spillage or penetrative drilling, is rarely reversible on any human timescale. Contaminants can persist for many decades, making the aquifer unsafe for human consumption and harming dependent ecosystems long after the industrial activity has ceased and the site has been restored. If it even is restored.

The magnitude of proposed mitigation, ranging from impermeable liners and sealed tanks to monitoring boreholes and detailed emergency response plans, implicitly acknowledges the fragility of the site. At some point, the need for extensive mitigation is itself evidence that the site is unsuitable for such development.

This concern is heightened by the application of the precautionary principle, a cornerstone of environmental planning. This principle holds that when there is uncertainty and the potential for serious or irreversible harm, the burden of proof lies with the applicant to show that harm will not occur. The planning system should not rely on hope that all safeguards will work flawlessly.

Procedural deflection: Yorkshire Water’s limited engagement

A recent direct response from Yorkshire Water to concerned local residents encapsulates the company’s limited engagement:

“We feel you may be better served making your representations to the Local Planning Authority so that your concerns may be raised as part of the planning process.”

This polite deferral signals a passive role, shifting responsibility away from Yorkshire Water’s statutory duty to protect water supplies. Despite awareness of the site’s sensitivity and hydrogeological risks, Yorkshire Water declines to take a firm stance, instead leaving the matter to be dealt with reactively by the Local Planning Authority.

Such procedural deferral undermines the precautionary principle and weakens public trust in their stewardship of vital water resources.

East Riding Council’s institutional failure

The East Riding of Yorkshire Council’s consultation response echoes these shortcomings. It raises no objection to the development, subject only to standard mitigation measures, despite the site’s location directly above a Principal Chalk Aquifer supplying drinking water to nearly a million people in their region.

ERYC’s response notably omits any reference to the site’s Source Protection Zone 3 (SPZ3) status, fails to require a robust, independently verified, up to date Hydrogeological Risk Assessment, and overlooks surface water and ecological impacts, including threats to the nearby Gypsey Race chalk stream, a significant and rare, sensitive chalk watercourse.

Such omissions directly conflict with the EYRC’s own planning policies, which emphasise precautionary protection of water resources and public health, and with national planning guidance.

Community evidence versus institutional complacency

The detailed consultation response from Foxholes & Butterwick Parish Council (F&BPC) starkly contrasts with the conditional or absent objections from statutory bodies. F&BPC highlights: it has

- the fractured chalk geology that enables rapid pollutant migration;

- the site’s position within Source Protection Zone 3, and the risk to local potable supplies and the ecologically sensitive Gypsey Race;

- the outdated and incomplete nature of the applicant’s Hydrogeological Risk Assessment;

- heavy reliance on unproven assumptions about well integrity and mitigation;

- lack of clear contingency planning for failure or extreme weather;

- absence of long term monitoring and restoration assurances.

This evidence-based stance underscores the accountability gap. It raises a fundamental question.

If those responsible for protecting Yorkshire’s water will not draw a clear line, who will?

Novel risks and the burden of proofing for our children

The chalk aquifers beneath the Yorkshire Wolds, as established and agreed by all parties, are regionally crucial, supplying drinking water to nearly one million people. A responsibility made more urgent by climate change pressures.

Yet, desktop research and consultations with the Environment Agency, BGS, and North Sea Transition Authority reveal a striking lack of precedent. While some wells, such as those at Wytch Farm, Horse Hill, and Broadford Bridge, may have penetrated chalk aquifers, there is no publicly verifiable example combining published borehole logs with local abstraction data confirming that a principal chalk aquifer supplying drinking water has been directly drilled through.

Egdon Resources’ claims to have done so elsewhere are therefore questionable. Their prior drilling may have affected adjacent or shallow chalk aquifers but not a principal drinking water source.

This is more than semantics. If Egdon’s proposal is a novel, untested case, the risks are unquantified and unprecedented. Regulators and developers have little historical experience to rely on, making the burden on the applicant to demonstrate airtight safety, monitoring, and emergency preparedness exceptionally high. Here, the precautionary principle must be rigorously applied.

National security context: Nature as a lynchpin

The stakes extend beyond regional water supply. The UK Government’s 2026 Nature Security Assessment on Global Biodiversity Loss, Ecosystem Collapse and National Security frames ecosystem degradation, including threats to vital water resources, as a matter of national security.

Ecosystem collapse jeopardises essential services such as drinking water, food production, economic stability, and social cohesion. The chalk aquifer beneath Foxholes is a critical natural asset underpinning resilience for nearly one million residents.

Yorkshire Water’s conditional acceptance of drilling, reliant on flawless post approval mitigation, conflicts starkly with this strategic imperative. The lack of unequivocal protection signals an institutional failure to align local planning with national priorities of ecosystem security and resilience.

Summary: Who will advocate for Yorkshire’s Water?

Yorkshire Water and East Riding Council acknowledge the extreme vulnerability of the Principal Chalk Aquifer beneath Foxholes. Yet both choose conditional risk management over risk avoidance, accepting industrial drilling subject to future safeguards and assumptions of perfection. This approach transfers potentially catastrophic consequences onto communities and future generations, who will bear the burden if safeguards fail.

When statutory bodies charged with protecting irreplaceable water resources cannot say “not here,” the planning system risks normalising industrial intrusion into critical natural assets. The precautionary principle demands that some places must remain off limits.

If Yorkshire Water will not draw a clear line in the chalk, and local authorities fail to enforce it, then the question is urgent and unambiguous:

Who is left to advocate for Yorkshire’s water?

Yorkshire Water response

DrillOrDrop put David Eddy’s concerns to Yorkshire Water. The company made the following statement:

“The proposed site is 10km from the nearest Yorkshire Water asset or water source. The applicant has proposed what we consider to be reasonable and sufficient mitigation to protect the Chalk aquifer and hydraulic fracking is not involved.

“As a result, it is our view that the risks to Yorkshire Water assets are very small and acceptable and as such, we would not be in a position to object to the planning application, due to the sufficient mitigation measures and distance from our sources.”

East Riding of Yorkshire Council

East Riding of Yorkshire Council responded as a statutory consultee on Egdon’s application for explore for gas at Foxholes. The council’s response did not comment on water quality or the risk of water pollution. It said it had no concerns about nature conservation or ecology, highways, odour, lighting, air quality or land contamination.

Categories: guest post, slider